R E R O U T E D

Data shows passengers being bumped off of flights is on the decline after United scandal

By Grace Manthey

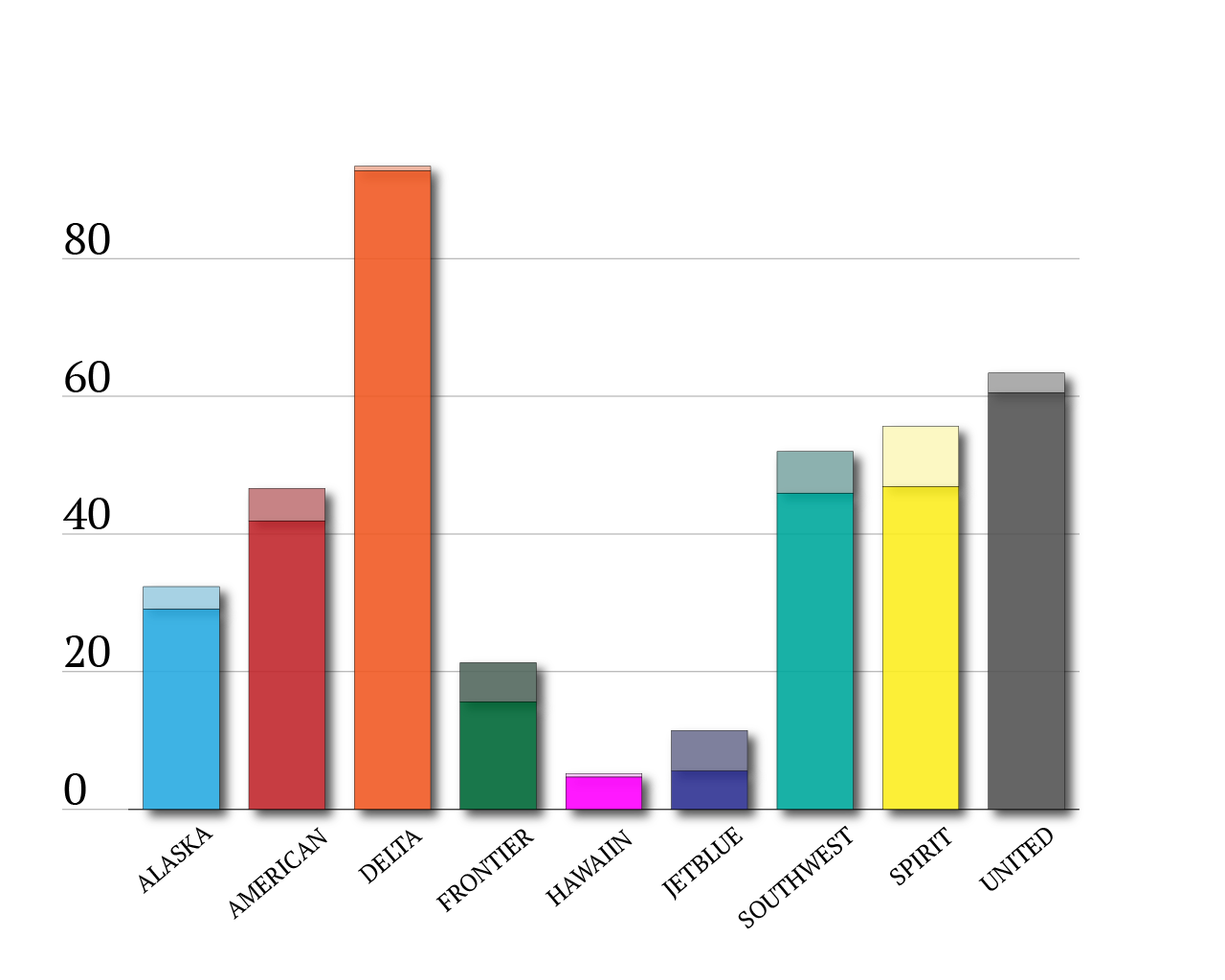

Overall rates of bumped passengers on decline

When security officers dragged a United Airlines passenger kicking and screaming off a flight in 2017, it turned into what some called a “PR nightmare.”

Following the scandal, an Annenberg Media analysis of public quarterly reports from the U.S. Department of Transportation showed a decline in passengers being bumped off of flights.

After the scandal, the company’s stocks dropped to a low of negative 4.3 percent two days into the crisis, according to Business Insider. It worked out to be about a $1 billion loss.

So, United announced it would start bumping fewer and fewer passengers, and other airlines seemed to follow suit.

Because even though the rate of bumping passengers wasn’t large to begin with, the consequences for doing it wrong certainly were.

Hover over the pie chart for more

Voluntary

vs

involuntary

bumping of passengers

6%

94%

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation

Fewer than four out of 100,000 passengers were bumped involuntarily in the last two years, contributing to only six percent of the total number of passengers that were denied boarding, according the DOT data.

And the last two years saw about a 50 percent decrease in the rates of passengers denied boarding on flights, for passengers that both volunteered to be bumped and those that did not. For just involuntary bumping alone, rates decreased by about 63 percent.

According to Matthew Trujillo, an information tech support specialist at Alaska Airlines, airlines across the board implemented changes following the United scandal, like increased training regarding bumping and overselling regulations.

Even though the number of overbooked flights isn’t relatively large, overbooking flights is no accident. It’s all driven by the airline’s bottom line.

Airlines study flights from the year before to determine how many people typically don’t show up, said Trujillo.

From there, the airlines can decide how many seats they can oversell by, but they make money from all the people who buy the tickets, including the ones that are predicted not to show up.

For example, if experts predict that two passengers will not show up for a flight, they cap flights at oversold by two. Assuming their prediction is right, the flight fills up. Then, two people don’t show up, and "boom! You’re good to go with a full flight!" said Trujillo.