By Christina Ungermann

December 13th 2017

“Development without displacement.” That’s the message Damien Goodmon, director of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition, wants people to remember about the organization’s fight against gentrification in his community.

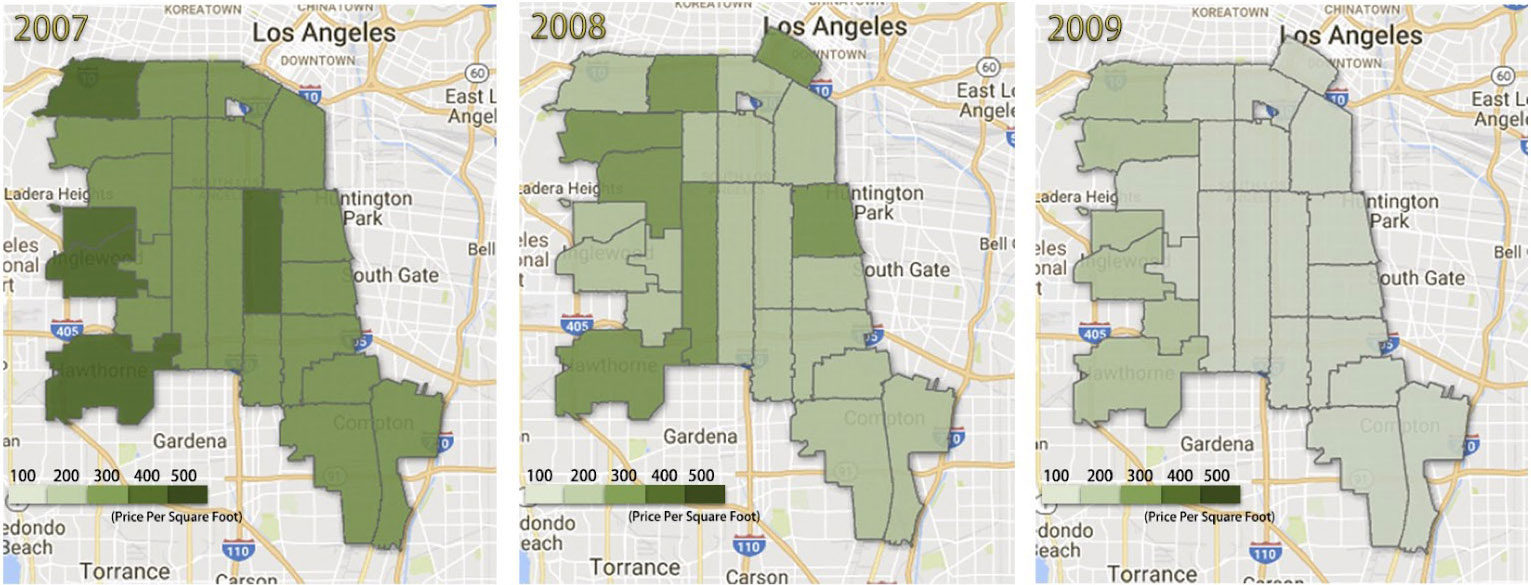

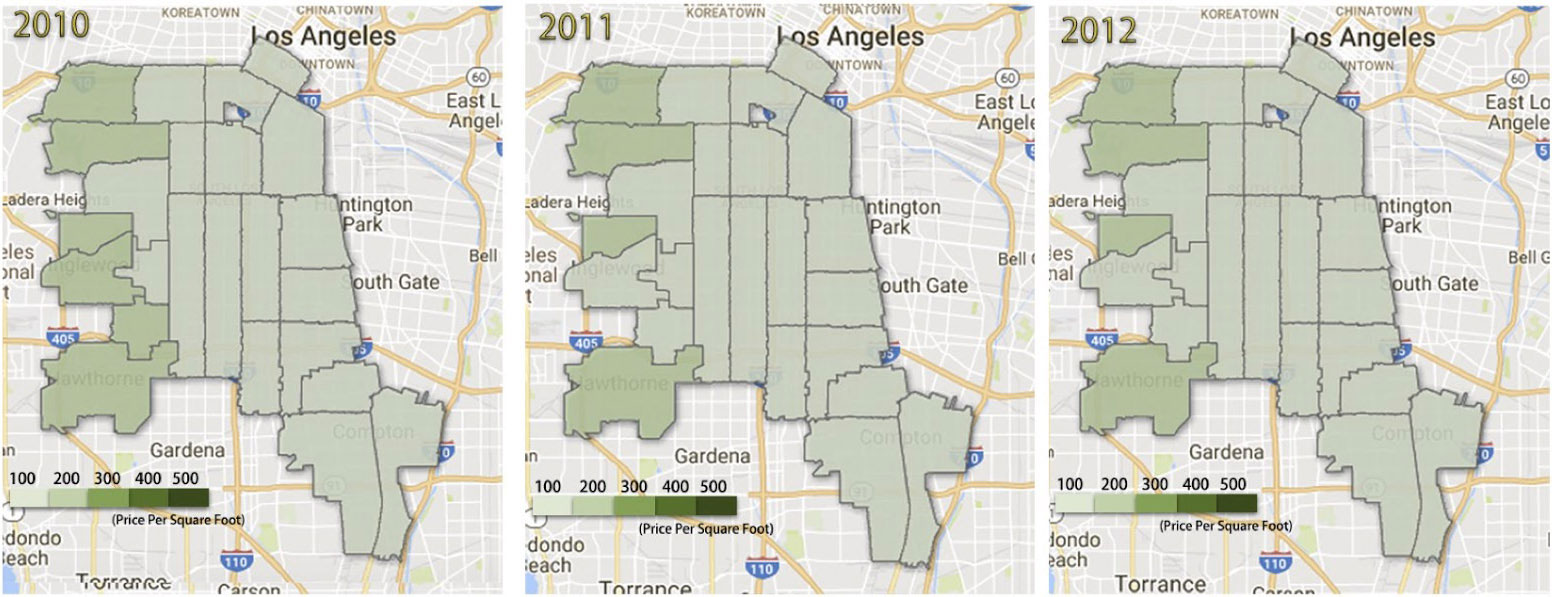

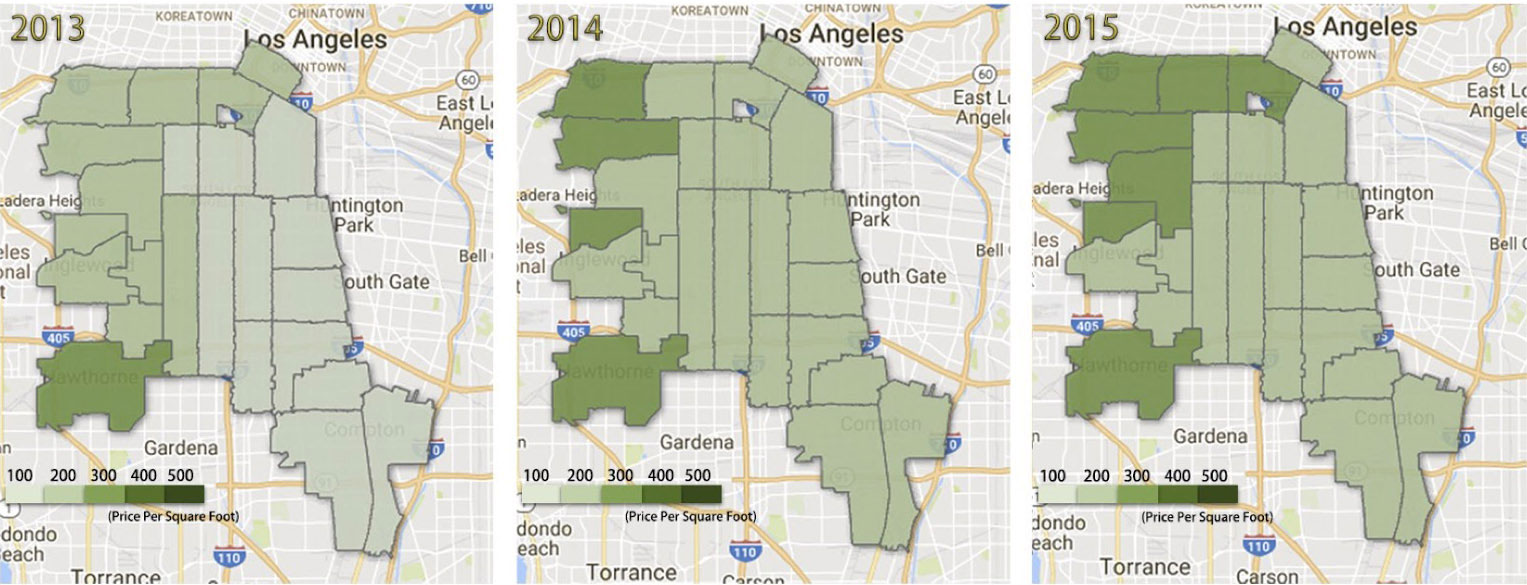

Recent developments in the Crenshaw/Baldwin Hills neighborhood of South Los Angeles, including the LA Metro Crenshaw Line that will connect the area to LAX and a proposed revamp to the community’s 70-year-old mall, are making some residents apprehensive about displacement.

“There’s no low-income community that wants to stay low-income,” Goodmon said. “But people don’t want to have to move away to find opportunities or to afford housing either — people just want better communities where they are.”

The layout for planned Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza $700 million renovation. It includes building roughly 1,000 condominiums, ten percent are reserved for low-income housing. (Photo courtesy of LA Department of City Planning)

The Crenshaw Subway Coalition seeks to enhance the development of the neighborhood without compromising the community that lives there. Goodmon said his group’s efforts are focused on educating residents about the imminent threat of gentrification and “building a broad coalition of groups to pressure out-of-state developers to come to the table and listen to our concerns.”

The biggest threat to the neighborhood, Goodmon said, is the proposed housing development planned by one of these out-of-state development companies, a Chicago-based real estate firm called Capri Capital Investors that owns the mall. The housing project is part of the massive $700 million renovation to Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, a shopping center at the corner of Crenshaw and Martin Luther King Jr. boulevards that opened in 1947. Capri Capital was unable to respond to a request for comment.

Construction by Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza. The renovation project hasn’t begun yet, but a light rail station LA Metro Crenshaw Line is being built next door and expected to open in 2019. (Photo: Christina Ungermann)

Luciralia Ibarra, senior city planner at the LA Department of City Planning, said the project will “lead to better housing choices for all.”

The proposed construction project includes building roughly 1,000 condominiums. Ten percent of those units, 100 condos, are reserved for low-income housing and the rest will be offered at market rate, according to the City Planning Commission, which is overseeing the project. Ibarra was unable to comment on the specific pricing of the condominiums.

Ibarra said that City Planning “is well aware of the pressure on the existing housing stock all of our communities face,” and that the city is “experiencing an unprecedented need to produce more housing to alleviate those pressures.”

But will the housing that the city and developers provide as a solution to these pressures truly benefit the majority of members in communities like the Crenshaw neighborhood?

The median household income in Crenshaw/Baldwin Hills is $37,948, one of the lowest-earning communities in the city, according to income figures in the LA Times neighborhood map of Los Angeles County.

To be eligible for low-income housing in Los Angeles, a person has to make no more than $50,500 per year, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. That qualifies most Crenshaw/Baldwin Hills residents for housing assistance.

With those numbers in mind, building 100 condos for low-income occupants into the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza revamp isn’t enough to meet community needs, Goodmon said.

“People will have to jump through hoops to get this housing, and yet we’re supposed to applaud these figures as though they are something to be cherished,” he said, using an example to explain. It’s like “having a dollar, and then I take 90 cents away and give them back 10. Would that make you happy?”

A Crenshaw Boulevard street sign near the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza. (Photo: Christina Ungermann)

Goodmon views the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza project as a continuation of a trend in Los Angeles: “the acquisition of mom-and-pop apartments in black and brown areas by large corporations.” This, he said, is because of a “yes by default” attitude in local government when it comes to greenlighting construction projects in low-income neighborhoods.

“There is a fear of gentrification and displacement in the community.”

— Luciralia Ibarra, senior city planner

The Crenshaw Subway Coalition sees this threat especially in communities with large percentages of people of color, like Crenshaw/Baldwin Hills. African Americans make up more than 70 percent of the neighborhood population, which is also 17 percent Latino, almost 5 percent Asian American and less than 4 percent white, according to the LA Times.

“It’s difficult to look at the aggressive tactics of those in the private sector and the apathy of those in the public sector who should be protecting black and brown people and not see the connection,” Goodmon said.

The LA Department of City Planning has “heard from community groups who have expressed concerns over the project,” said Senior City Planner Ibarra. She added that the government body recognizes that “there is a fear of gentrification and displacement in the community.”

In addition to including 100 low-income units in the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza development, Ibarra said, the city government is “advancing a number of long-lasting strategies to ensure housing is affordable at all income levels.”

City Planning hopes to streamline the process for receiving low-income housing, she said. California is also working to incentivize the creation of more affordable residences through the Density Bonus Program, which allows developers to build housing beyond what zoning laws would normally allow if they include a certain amount of low-income housing.

The Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza housing development is an example of this law in action.

While these efforts may be a step in the right direction, activists like Goodmon argue that the only true way to have development without displacement is to include community members in the planning of construction projects.

Ibarra of City Planning said her department has done this by “holding a number of workshops and informational meetings to obtain ideas and solutions to our challenges.” But the Crenshaw Subway Coalition maintains that such efforts don’t get to what they say is a huge issue: Large out-of-state investors will never truly understand the needs of the neighborhood.

“The root of the problem is that housing is currently a commodity, and profit motives lead to market manipulation by these companies,” Goodmon said. His organization focuses on countering this by “advocating for policies that change how we think about development,” he said.

The Crenshaw Subway Coalition’s website contains a letter that the organization, along with 79 other community groups, sent to LA legislators including Mayor Eric Garcetti, city planning commissioners and others. It implores the city leaders to put a hold on the mall’s renovation project until a health impact assessment is conducted.

The coalition states, on its website, that this assessment would answer lingering questions about “how many residents are at risk of being placed in further financial strain and/or indirectly displaced (a type of displacement that occurs when residents and businesses are gradually priced out/harassed out of the area and must involuntarily leave).”

The letter was sent in May but there has been no attempt to conduct a health assessment, according to the group’s website, and the project is expected to move forward as planned.

Many community members are dissatisfied with what they see as paltry efforts by local government to curb gentrification. Eddie Stokes, an artist who was hanging out at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza on a recent weekday afternoon, said that government officials and those in the private sector are “taking people that are already here and moving them like chess pieces.”

Eddie Stokes, an artist who was hanging out at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza on a recent weekday afternoon, said that government officials and those in the private sector are “taking people that are already here and moving them like chess pieces.” (Photo: Christina Ungermann)

He is not totally opposed to development in the community. “You always need to update your infrastructure to accommodate the next generation,” he said. But Stokes does have a problem with those who “don’t make accommodations for those with lesser means,” adding that “there’s a problem with their thought process.”

Another visitor to the mall, David Felix Fisher, said he moved to Crenshaw/Baldwin Hills from New Orleans in 2005 after losing everything in Hurricane Katrina. He has been battling homelessness and housing insecurity ever since.

Fisher sees his living situation, and the city’s current housing crisis, as a symptom of racism. “LA is one of the most racist places I’ve been in the whole United States, and I’ve been a lot of places,” he said.

David Felix Fisher said he moved to Crenshaw/Baldwin Hills from New Orleans in 2005 after losing everything in Hurricane Katrina. He has been battling homelessness and housing insecurity ever since. (Photo: Christina Ungermann)

“Zillionaires don’t want to live right next to low-income people. Their lifestyles are very different. They don’t want low-income people living in this mall.”

— David Felix Fisher

Both Stokes and Fisher talked about fundamental misunderstandings between that haves and have-nots, as well as between white people and people of color.

“Zillionaires don’t want to live right next to low-income people. Their lifestyles are very different,” Fisher said. “They don’t want low-income people living in this mall.” He added that even though there are plans to include some low-income housing, eventually the new development will likely bring up prices and push people out anyway.

Stokes sees the wealthy as having a “not in my backyard” mentality, while the poor “start to resent you when you push them out,” he said.

The artist also sees a connection between racial prejudices and misunderstandings.

“People seem to forget that historically, black people were not allowed to move in [to suburbs] and you had white flight [from urban areas],” he said. The issue is now, after decades, “white people want to move back in,” which can perpetuate tensions between current and future residents.

Stokes acknowledged that this trend of migration is to be expected, but he said that doesn’t stop it from being a highly disruptive process, especially without proper regulation.

If there is to be any hope for developing in low-income communities in a way that satisfies all the stakeholders, “everyone has to stand as one,” Fisher said. “The humiliation, the hatred, the racism all have to go.”

While it’s doubtful that a fundamental change of that scale can occur before the new Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza is completed, activists and community members will continue to work toward a sustained cooperation with the city government and developers on this project as it gets further along in the building process, along with more large-scale developments in the future.